Learn Rust by reading a server Code

Connected Post

Let’s not build a server from scratch but read source code in Rust

Intro

Last time we’ve read through the “main.rs” code. [1], [2] In the main function, we create “default_path”, “public_path”, and “server” variables. The first two variables (“default_path” and “public_path”) are deterministic. In this post, we are going to go deep what “server” variable is. Let’s open the “server.rs” file. [3]

We are only focusing on the “server.rs” file accepting the request using TCP Listener as a bytes stream. The parsing process will be handled in another post. In the post, we can take a look at how error handling works in Rust.

Line number 1 to 17

use crate::http::{ParseError, Request, Response, StatusCode};

use std::convert::TryFrom;

use std::io::Read;

use std::net::TcpListener;

pub trait Handler {

fn handle_request(&mut self, request: &Request) -> Response;

fn handle_bad_request(&mut self, e: &ParseError) -> Response {

println!("Failed to parse request: {}", e);

Response::new(StatusCode::BadRequest, None)

}

}

pub struct Server {

addr: String,

}

Let’s read the code line by line.

“use” keyword

use crate::http::{ParseError, Request, Response, StatusCode};

use std::convert::TryFrom;

use std::io::Read;

use std::net::TcpListener;

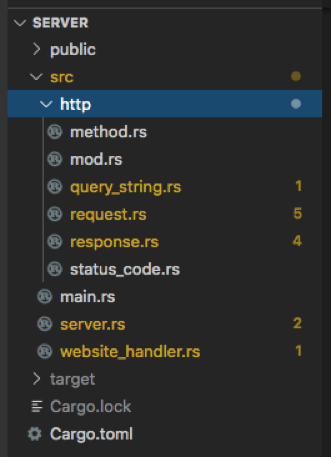

To follow this source code, we need to check the folder structure. The “std” means standard and it does not need to follow up the structure, but it is required to understand the “crate”. The “crate” means the root of this crate, current project. In this case, the “http” module will be expected at the root of this crate. It points this folder. Since “mod.rs” file is in the “http” folder. We can find the declare statements of those modules inside of curly brackets (“ParseError”, “Request”, “Response”, and “StatusCode”).

“pub” keyword

pub trait Handler {

// ...

}

Visibility in Rust is conservative. The default setting in Rust is private. Until explicitly changing one’s visibility in public using “pub”, it’s not accessible by the outside. And it does not escalate in the children of the module. We should use the “pub” statement to the children of the “pub” module.

“trait” statement

pub trait Handler {

fn handle_request(&mut self, request: &Request) -> Response;

fn handle_bad_request(&mut self, e: &ParseError) -> Response {

println!("Failed to parse request: {}", e);

Response::new(StatusCode::BadRequest, None)

}

}

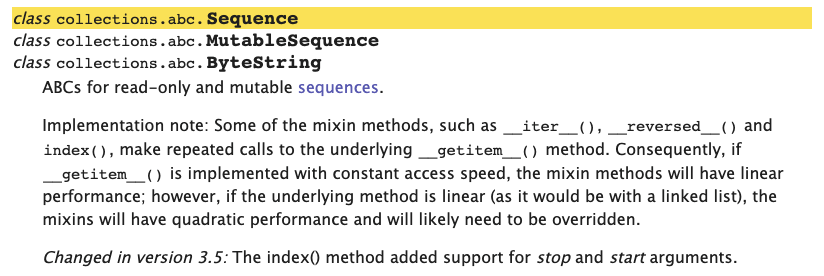

In the official document, a trait is a collection of methods defined for an unknown type: Self. They can access other methods declared in the same trait. [4]

I understand a trait in Rust is like an interface in object-oriented languages. It’s not the concrete instance, but it helps what method should be declared in the struct. If a struct uses the “Handler” trait, the struct must define the “handle_request” function in this case. The “handle_bad_request” function will be used as it is. It is a default method. The method name is self-documenting and we are not going to take a look at what the “Response” and “ParseError” are. In this post, we are going to focus on reading the source code of the “server.rs” file. So, remainings will be mentioned in another post. The concept of the “Handler” processes all kinds of responses. If it is valid, the “handle_request” function is used. If not, the “handle_bad_request” function will be called.

“struct” keyword

pub struct Server {

addr: String,

}

A struct, or structure, is a custom data type that lets you name and package together multiple related values that make up a meaningful group. [5]

I can say a struct is a collection of variables. Each of them has a strong relationship. If it does not have any relation, the cohesion of the code will be harmed. It means the readability of source code is bad.

In the code, we only need a variable that stands for the address of the server. You said it’s a collection of variables, but it’s just a variable. Why should we use struct? I think to collect related functions in one place. It’s for creating a reusable code, maintenance, and readability.

Recently, I read a classic book; Code Complete. While reading the book, I understand one way to create a better source code is readability. The well-written code will be self-documenting. If you are interested in a topic about how to create a better quality source code, please check out the book.

Line number 19 to 53

impl Server {

pub fn new(addr: String) -> Self {

Self { addr }

}

pub fn run(self, mut handler: impl Handler) {

println!("Listening on {}", self.addr);

let listener = TcpListener::bind(&self.addr).unwrap();

loop {

match listener.accept() {

Ok((mut stream, _)) => {

let mut buffer = [0; 1024];

match stream.read(&mut buffer) {

Ok(_) => {

println!("Received a request: {}", String::from_utf8_lossy(&buffer));

let response = match Request::try_from(&buffer[..]) {

Ok(request) => handler.handle_request(&request),

Err(e) => handler.handle_bad_request(&e),

};

if let Err(e) = response.send(&mut stream) {

println!("Failed to send response: {}", e);

}

}

Err(e) => println!("Failed to read from connection: {}", e),

}

}

Err(e) => println!("Failed to establish a connection: {}", e),

}

}

}

}

It looks like pretty a lot but let’s divide and conquer to understand what’s going on.

“Genius is eternal patience.” – Michelangelo

“impl” keyword

impl Server {

// ...

}

The impl keyword is primarily used to define implementations on types. Inherent implementations are standalone, while trait implementations are used to implement traits for types, or other traits. [6]

I understand the “impl” keyword is giving a shape to the blueprint of a struct. Most related functions are declared using the “impl” keyword.

new function

pub fn new(addr: String) -> Self {

Self { addr }

}

According to the document, the “Self” keyword is that the implementing type within a trait or impl block, or the current type within a type definition. [7] So, the “Self” means the “Server”. The author uses “new” same as other object-oriented languages, but actually, we can name it any(“create”, “origin”, and “instantiate”). This is a short-hand way to instantiate the actual Server type. The full version of it is below instantiating with the given the “addr” parameter. The last expression is the return value.

Self {

addr: addr

}

Let’s recall the main function.

let server = Server::new("127.0.0.1:8080".to_string());

We can say the statement is instantiating the “Server” variable.

run function

pub fn run(self, mut handler: impl Handler) {

println!("Listening on {}", self.addr);

let listener = TcpListener::bind(&self.addr).unwrap();

loop {

// ...

}

}

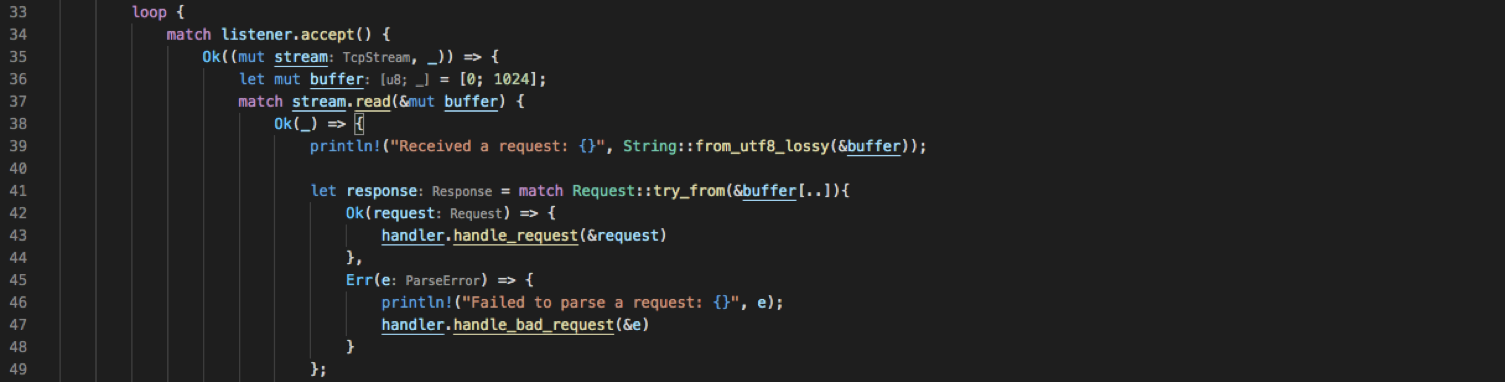

To make it easy to understand, I commented out inside of the loop. The original code is here.

The “run” function takes two parameters. One is self and handler. “handler” should be a type that implements the “Handler”. The “println!” macro prints out the server address.

The “bind” function is explaind in the documentation. “Creates a new TcpListener which will be bound to the specified address. [8]” We can find what “unwrap” function is. “Returns the contained Some value, consuming the self value. [9]” Hense, if the “self.addr” is a valid address to bind, it returns the “TcpListener”. If not, it goes to panic. We can make it strong by adding a validity check logic for the address value.

The “loop” is a keyword to create an infinite loop. [10] Ok. When the “run” function calls, the server instance will run forever and try to get some request.

“match” keyword, inside of loop

match listener.accept() {

Ok((mut stream, _)) => {

// ..

}

Err(e) => println!("Failed to establish a connection: {}", e),

}

The “match” keyword is explained. “Rust provides pattern matching via the match keyword, which can be used like a C switch. [11]” Rust compiler forces to handle all kinds of branches.

For me, it’s beyond the switch in C since I can use the match keyword to find a string, error, and value of Enum. The “listener” variable is the TcpListener. It calls the “accept” function and the accept function can return the Result type. The Result type is a core to handle error in Rust. Since the match keyword forces to handle all types of results, this combination must handle success and failure cases without losing the logic.

According to the official document, the “listener” accept a new incoming connection [12]. When the return value is invalid, the “Err” arm is matched. The sentence “Failed to establish a connection: error” will be shown in the console. It returns a tuple stream and the address when it is valid.

inside of listener.accept(), valid case

Ok((mut stream, _)) => {

let mut buffer = [0; 1024];

match stream.read(&mut buffer) {

Ok(_) => {

// ...

}

Err(e) => println!("Failed to read from connection: {}", e),

}

}

The “accept” function returns stream and address, if there’s no problem. Since we are not interested in the address, we can ignore it using the underbar. We define a buffer variable to read the stream by filling all with 0. It means that creating a zero value array with 1024 sized. [13] The “mut” means mutable the value of buffer is changeable. Because we are going to read the stream using the buffer, it makes sense.

inside of stream.read(), valid case

Ok(_) => {

println!("Received a request: {}", String::from_utf8_lossy(&buffer));

let response = match Request::try_from(&buffer[..]) {

Ok(request) => handler.handle_request(&request),

Err(e) => handler.handle_bad_request(&e),

};

// ...

}

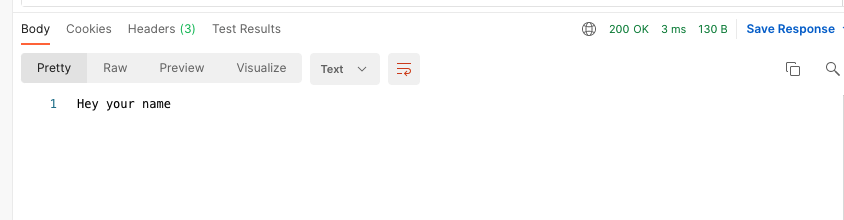

The “stream.read” function returns how many bytes were read. We don’t care about how many bytes, but we care about what’s the request is. The first “println!” macro shows the request. The “from_utf8_lossy” function under the “String” crates converts bytes to string. The string should be valid UTF-8. Here’s a reference post about the string type in Rust.

The “try_from” function performs the conversion. [14] We want to convert bytes to a valid Request type. Then, the “Request” will be handled by one of the handler functions; “handle_request” or “handle_bad_request”. As we saw the Handler trait, the return type of two functions is the “Response”. Whatever “Response” is returend is stored in the “response” variable.

inside of stream.read(), if let keyword

if let Err(e) = response.send(&mut stream) {

println!("Failed to send response: {}", e);

}

match response.send(&mut stream) {

_ => (),

Err(e) => println!("Failed to send response: {}", e);

}

These two snippets of codes are the same. When there’s an error in sending the response, it prints out the error message in the console. The if-let keyword is the shorthand version of the match keyword, but may not always applicable.

Outro

The first time I saw the server code, I thought that why the tons of match keyword is everywhere. Writing this article makes me understand that it’s useful to debug every detail step and it’s strong enough to track all kinds of errors. Let me close this post with the same quote and the remainings will be covered in other posts.

“Genius is eternal patience.” – Michelangelo

References

[1] https://github.com/gavadinov/Learn-Rust-by-Building-Real-Applications/blob/master/server/src/main.rs

[2] https://devjunhong.github.io/rust/lets-not-build-a-server/

[3] https://github.com/gavadinov/Learn-Rust-by-Building-Real-Applications/blob/master/server/src/server.rs

[4] https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/trait.html

[5] https://doc.rust-lang.org/book/ch05-00-structs.html

[6] https://doc.rust-lang.org/std/keyword.impl.html

[7] https://doc.rust-lang.org/std/keyword.Self.html

[8] https://doc.rust-lang.org/std/net/struct.TcpListener.html#method.bind

[9] https://doc.rust-lang.org/std/option/enum.Option.html#method.unwrap

[10] https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/flow_control/loop.html

[11] https://doc.rust-lang.org/rust-by-example/flow_control/match.html

[12] https://doc.rust-lang.org/std/net/struct.TcpListener.html#method.accept

[13] https://doc.rust-lang.org/std/primitive.array.html

[14] https://doc.rust-lang.org/std/convert/trait.TryFrom.html#tymethod.try_from

Leave a comment