Docstring, Variable Arugments, Lambda, and Keyword only arguments

Docstring

def myFunction(arg1, arg2=None):

"""myFunction(arg1, arg2=None) ->

Doesn't really do anything, just prints.

Parameters:

arg1: the first argument.

arg2: second argument. Defaults to None.

"""

print(arg1, arg2)

def demo_docstring():

print(map.__doc__)

# docstring of map function

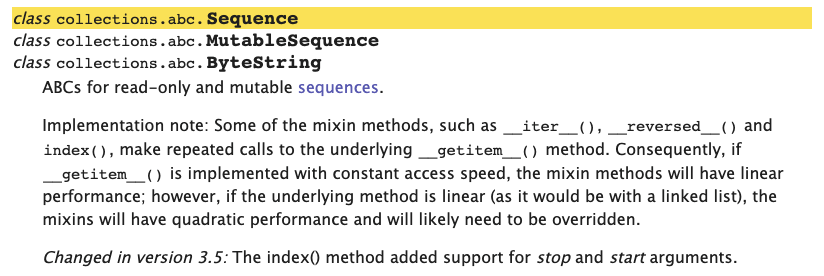

import collections

print(collections.__doc__)

# docstring of collections module

print(myFunction.__doc__)

# docstring of custom function;

# the triple quotes next line from myFunctions

demo_docstring()

A docstring is a manual for modules, functions, and classes. Writing a manual is a quite tedious thing to do but it’s beneficial when you back to the old code. Although you write the code, you may not remember all the details and brushing up your brain will consume your valuable time. We can also find docstring from the built-in functions. Here is the best practice for docstring; PEP 257. In this post, this is a brief list of the best practice.

- Enclose docstrings in triple quotes

- First line should be a summary sentence of functionality

- Modules: List important classes, functions, exceptions

- Classes: List important methods

Functions

- List parameters and explain each, one per line

- If there’s a return value, then list it; otherwise omit

- If the function raises exceptions, mention those

Using Variable Arguments

def addition(*args):

result = 0

for arg in args:

result += arg

return result

def my_addition(base, *args):

result = 0

for arg in args:

result += arg

return result

def demo():

print(addition(5, 10, 15, 20)) # 50

print(addition(1, 2, 3)) # 6

my_nums = [5, 10, 15, 20]

print(addition(*my_nums)) # 50

print(my_addition(*my_nums)) # 45

demo()

If we don’t know how many parameters will be, then we can design a function to take variable numbers of parameters. Using ‘*’ mark in front of parameters, it means we can pass variable numbers of parameters. But be careful when you change a signature of function for example in ‘my_addition’ function in the above code, it results unexpected behavior. This kind of unexpected behavior is usually really hard to catch. Please take care when you change it.

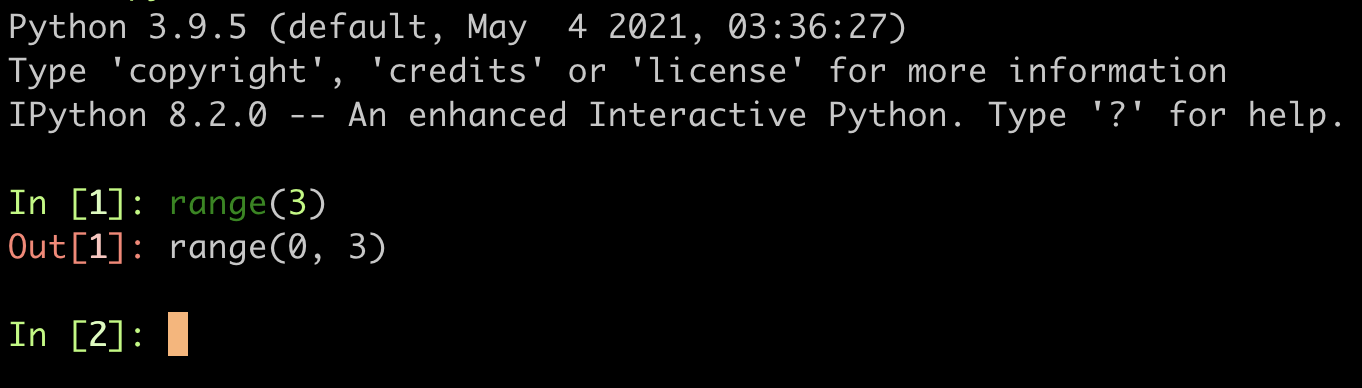

Lambda functions

def CelsiusToFahrenheit(temp):

return (temp * 9 / 5) + 32

def FahrenheitToCelsisus(temp):

return (temp - 32) * 5 / 9

def demo():

ctemps = [0, 12, 34, 100]

ftemps = [32, 65, 100, 212]

print(list(map(FahrenheitToCelsisus, ftemps)))

# [0.0, 18.333333333333332, 37.77777777777778, 100.0]

print(list(map(CelsiusToFahrenheit, ctemps)))

# [32.0, 53.6, 93.2, 212.0]

print(list(map(lambda t: (t - 32) * 5 / 9, ftemps)))

# [0.0, 18.333333333333332, 37.77777777777778, 100.0]

print(list(map(lambda t: (t * 9 / 5) + 32, ctemps)))

# [32.0, 53.6, 93.2, 212.0]

demo()

We can make code more readable by using the lambda function. If we have experience in C# or Java, we can catch this concept easily. While we are programming in C# or Java, we might use anonymous function and that’s it. It can pass to function as an argument and it’s one line of code. It makes our code simple and clean.

Keyword-only arguments

def my_function(arg1, arg2, *, suppressExceptions=False):

print(arg1)

def demo():

# First, this works and prints 1

my_function(1, 2, suppressExceptions=True)

# Second, Error!, we need to call this in explicit way

my_function(1, 2, True)

demo()

We can design a function that is called by only explicit way. The ‘*’ mark in front of the argument. It’s the keyword-only arguments. In the above code, I used ‘*’ in front of the ‘suppressExceptions’ argument. When I call this function I should call it with the keyword just like the first call. The second call raise an error.

TypeError: my_function() takes 2 positional arguments

but 3 were given

Leave a comment